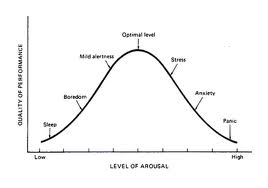

One of the reasons that caffeine is not a drug of abuse is that, unlike cocaine, amphetamine, or heroin, caffeine does not produce effects that indefinitely increase as you increase the dose. Caffeine has a built in mechanism that guarantees that a little does a little, more does more, but even more starts to reverse the beneficial effects and does less! For example, a runner who uses a little caffeine can run further and faster than if he did not. If he takes still more caffeine, he can run still further and still faster. However, if he takes too much caffeine, his performance will suffer, and he will run slower and less far. This pattern of responses is called the “Yerkes-Dodson Effect.” This effect was originally used to describe the outcomes of different levels of arousal, ranging from sleep and mild arousal, to stress, and, finally, reaching anxiety and panic. According to this schema, our arousal levels can be increased to an optimal level producing optimal performance. However, if they are increased still further, stress, anxiety, and finally panic is experienced, and our performance suffers. When represented as a graph, it looks something like an inverted “U.”

The beneficial effects of caffeine can be graphed in a parallel way to arousal levels:

But the question every person has to answer for himself is: What is my optimal level of caffeine intake? How much caffeine will produce the maximum benefit for me?

Introverts are more sensitive to caffeine than extroverts. Therefore, all other things being equal, it requires less caffeine for an introvert to achieve the optimal benefit than is required for an extrovert to achieve the optimal benefit. For example, an extrovert’s optimal level might be 400 milligrams of caffeine, while the same dose might be well past the optimal point for an introvert.

Many factors influence the level that is optimal for each person. For example, taking birth control pills makes you more sensitive to a lower dose of caffeine.

To find out the full story of how caffeine’s effects are changed by the medicines you take, the foods you eat, your personality, your state of health, your genetic heritage, and so on, check out our book The Caffeine Advantage: How to Sharpen Your Mind, Improve your Physical Performance, and Achieve Your Goals–the Healthy Way.

Well, Bennett, I seem to be a test case for this effect. I’ve taken the test three times. The first time, on March 28th, I had a large (16 oz.) cup of coffee. Before my coffee I scored an 11, and after my coffee I scored an 11, for no change. You recommended that I try a larger dose of caffeine, so the second time, on April 4th, I had two large (16 oz.) cups of coffee. This time, before my coffee I scored a 10, but after my coffee I scored only an 8, a significant decrease in improvement. This time in response you mentioned the Yerkes-Dodson Effect, and hypothesized that I took too much caffeine. So my third try, today on April 16th, I tried a medium cup of coffee (10 oz.). Before my coffee I scored a 9, and after my coffee I scored an 11, a significant improvement.

Bravo! Thanks so much for giving this a real try. I think the Yerkes-Dodson effect is alive and well and really does govern what we see as a result of using caffeine.